As adults, we often step into particular kinds of roles with children. We can be parents, aunts, uncles. We can be coaches, mentors, teachers. Each role has a set of expectations, often with an unspoken rule that the adult knows best and that children will learn from us.

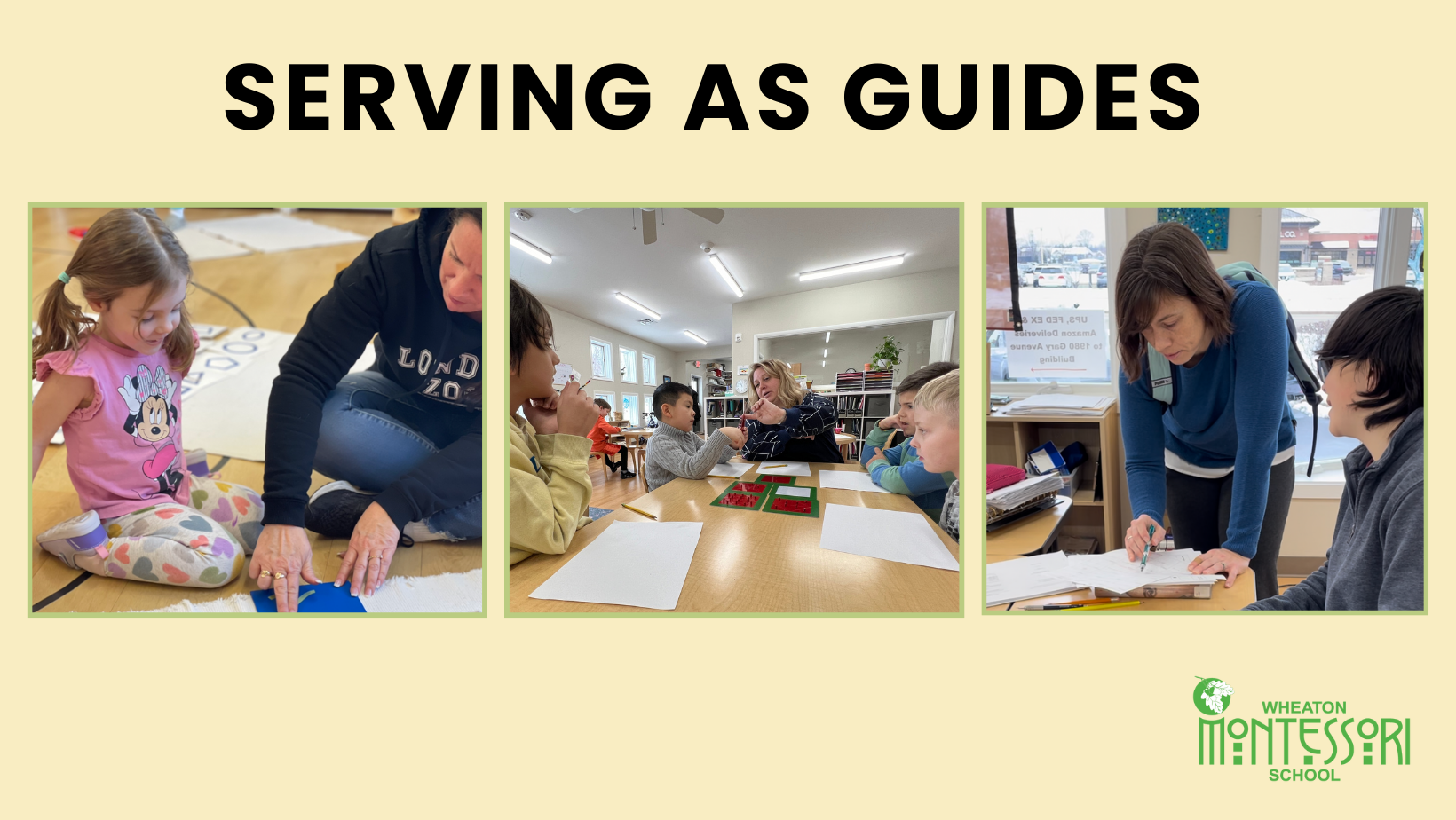

The roles adults play in children’s lives are much more nuanced. We facilitate, suggest, model, and observe. The world can teach, and adults can serve as guides in the process of learning and discovery.

Be Curious

One way adults guide growth and learning is by asking “curiosity questions.” Genuinely curious questions may begin with a script and then become authentic. Try asking questions like:

- How do you feel about what happened?

- What were you trying to accomplish?

- What did you learn?

- How do you think you might use what you learned?

- What ideas do you have for solutions?

Avoiding the question “Why?” is also important as it can sound accusatory and can lead to a child feeling defensive.

Sometimes a young person in our life is struggling. We can shift our approach to ask what ideas they can share with us based on their needs and our needs. We can be curious about what they want or need in the interaction. For example, sometimes when a young person is struggling, we want to know how we can help that person feel better. When that is the case, ask: “What can I do to help you have a better day?” Maybe the response will be within our powers and if not, we can acknowledge the idea and offer two manageable options.

Shift to Support

When we shift our roles and think about how to learn more about what our children are feeling, thinking, and exploring, we become meaningful guides. Rather than providing information, we can help children make discoveries. This is an essential part of what Montessori teachers do each day in our learning communities. The process of adults serving as guides during learning and discovery starts as young as when children are in Preschool and continues through our Adolescent Community at Wheaton Montessori School.

Preschool students are carefully guided to take ownership of their learning. One of the instances when these young students are directed to assume responsibility for their learning is when they are working with the movable alphabet. Very young students can pull together experiences with letter recognition, letter sounds, and story-telling experiences while working with the moveable alphabet. Their fine motor skills may not permit them the coordination to write on paper, but they have the preformed letters to build words, phrases, and stories.

Our elementary-aged children, 1st-6th graders, make amazing connections during their learning journeys. An elementary student can be ecstatic over a discovery about the periodic table, as recently happened with a young learner: “Look!” she exclaimed. “Gold has the symbol Au because the Latin name for gold is aurum. Au for aurum!” Because this young person had discovered this connection on her own, the knowledge was so much more invigorating and inspiring than had an adult instructed her about etymology and periodic table symbols. This student took ownership of the information that had been led through multiple indirect lessons.

Adolescents Community students work side by side with their teachers Mrs. Kelly Jonelis and Mrs. Lauren Vincenti daily planning the weekly lunch plan, budgeting, shopping for ingredients, cooking, serving, and enjoying lunch as a class. These students are gaining practical life skills while adults are there to guide them and offer support when needed. Experiences are gained and immediate peer feedback is available in an inclusive and supportive environment. For example, while prepping carrots for a meal according to the instructions in a recipe, they have the freedom to cut these carrots in another style where they gain experience and are open to receiving peer feedback in an inclusive and supportive environment. These adolescents are guided by adults to learn about responsibility and the outcomes of their actions in a suitable and organized setting.

Guiding students of any age is often a fine line between freedom and structure. Setting up as much underlying structure as possible will increase the amount of self-discipline that develops. As they can handle more responsibility, they are permitted greater independence to learn through their experiences.

Honor the Process

In How Children Learn, John Holt describes children’s process of learning: “The child is curious. He wants to make sense of things, find out how things work, gain competence and control over himself and his environment, and do what he can see other people doing. He is open, perceptive, and experimental. He does not merely observe the world around him. He does not shut himself off from the strange, complicated world around him, but tastes it, touches it, hefts it, bends it, breaks it. To find out how reality works, he works on it. He is bold. He is not afraid of making mistakes. And he is patient. He can tolerate an extraordinary amount of uncertainty, confusion, ignorance, and suspense.”

Mrs. Tracy Fortun spoke about this last month at our Better Together Get-Together event. If your schedule doesn’t allow you to attend, she recommends observing when a child is experiencing frustration without jumping in. Ask yourself, “What am I tempted to do or to “fix” it for them? Are they capable of taking care of it themselves? What would my normal response be, and how might that steal their opportunity to learn to cope with frustration”. Children should be provided with an opportunity to learn how to cope with frustration, thus increasing their tolerance level when faced with uncertain situations. Through this guidance, adults are permitting frustration tolerance which leads to emotional maturity.

Children naturally want to figure out the world and themselves. we can be thoughtful guides through this remarkable world of ours. We can entice. We can inspire. We can show possible paths.

At Wheaton Montessori School, we recognize the incredible power in the children’s process of experimenting, observing, making mistakes, learning from them, and discovering the world around them. Rather than serve as the experts dispensing knowledge, Wheaton Montessori School teachers act as guides to expose, curate, structure, and provide experiences to children in scientifically proven ways.

We invite interested parents of young children wanting to join Wheaton Montessori School to schedule a tour to see how we support our students from preschool through high school freshman year in nuanced ways. Schedule your school tour by clicking this link and see our teachers serving as guides and how our children take responsibility and ownership during this learning process.

Current families are invited to schedule their classroom observation by clicking the green buttons below. During your classroom visit, you will notice the guidance provided by our teachers as mentors and see the responsibility and drive displayed by our students during their learning process.