Nestled on a shelf in our preschool and kindergarten classrooms (and elementary shelves) you’ll find a small wooden cabinet with six slim drawers. It may not look like much from the outside. Even when you slide out one of the drawers, you’ll see six square wooden divisions each with a blue wooden inset with a small knob in the center. As you continue to pull out the different drawers, you’ll discover that each wooden inset is a series of geometric shapes: circles that vary in diameter, rectangles with the same height but varying in width up to the square, different triangles, regular polygons, quadrilaterals, and curved figures.

This is the Geometry Cabinet, an important and well-used material in Montessori primary (and elementary) classrooms. With a multitude of uses, this material serves to help children not only enhance their visual and muscular memory but also provide a foundation for advanced geometry work and preparation for handwriting.

The Foundation for Geometry

First and foremost, the geometry cabinet introduces plane geometry. Often, the initial lesson will be the equilateral triangle, square, and circle. These first shapes form a foundation in geometry: the circle calculates angles, the triangle constructs, and the square measures area.

Another fun and detailed way to think about these three shapes is in terms of polygons. The equilateral triangle is the polygon with the least possible number of sides. The circle can be thought of as a polygon with infinite sides. The square represents the rest of the polygons. Of course, these facts are explored in our elementary communities. In the primary classroom, we use these distinct forms to provide children with the first impression of the three fundamental shapes in geometry and to introduce how to use the entire geometry cabinet. Imagine all of the built-in choices children have to follow up on. Wheaton Montessori students move quickly beyond the three introductory shapes.

A Tactile Experience

One of the first things we do with the geometry cabinet is demonstrate how to use the knob to pick up the shape with the non-dominant hand and then trace the whole perimeter of the shape with the index and middle fingertips of the dominant hand. We also show how to trace the outline of the aperture that the shape fits into. This careful, meditative action is designed to both give children a tactile impression of the shape and to help them develop the fine motor control necessary for writing.

Once children have this experience with a few shapes, they move on to tracing and matching the shapes from a whole drawer and then even mixing up the shapes from multiple drawers to trace and match into their aperture. When children get good at this process, we introduce taking away the visual sense by wearing a blindfold!

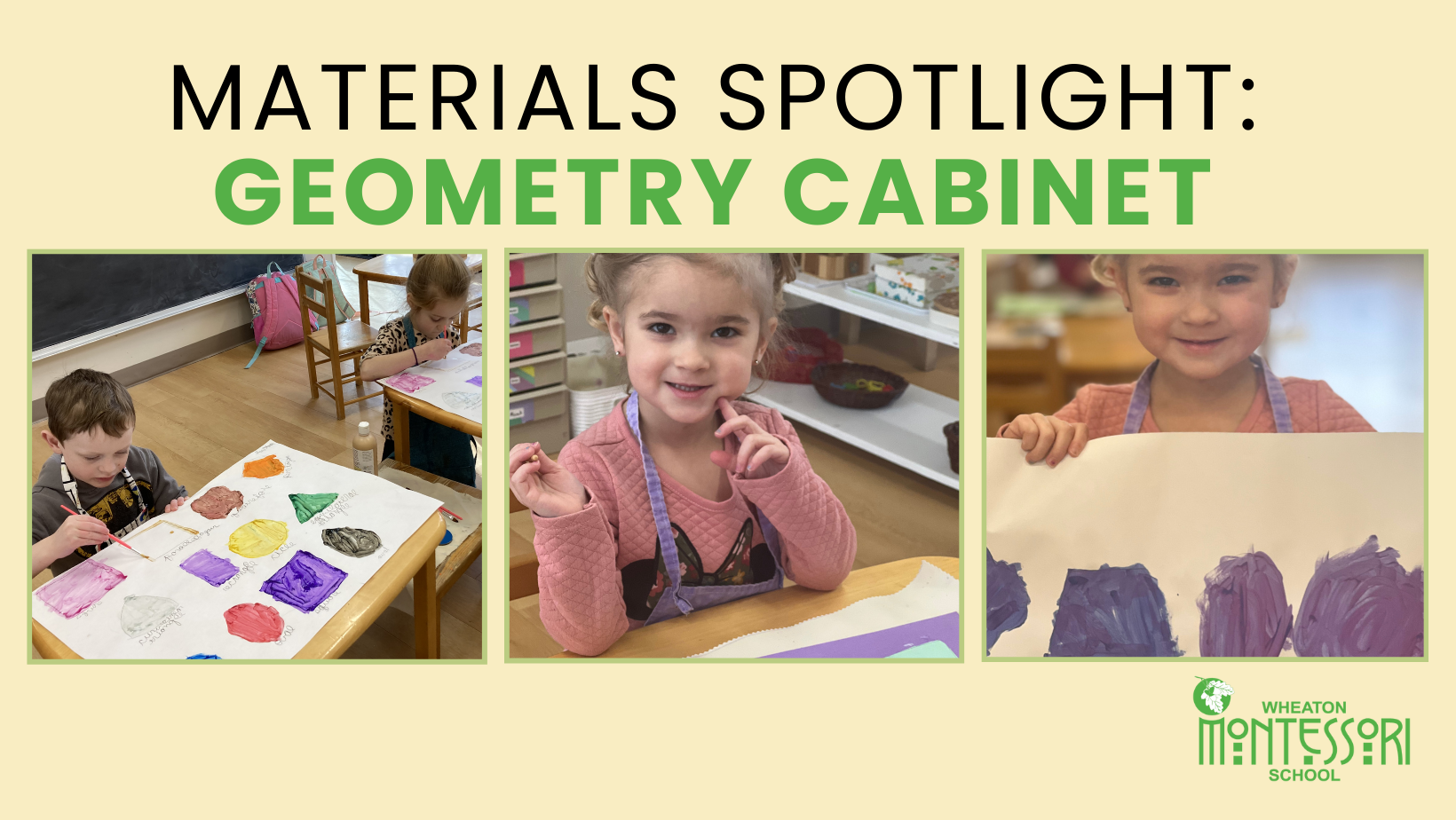

One of our Preschool and Kindergarten teachers, Ms. Chiste said “ The student’s favorite thing to do is paint each of the shapes them”.

From Concrete Objects to Abstract Symbols

We also introduce sets of cards for each geometric shape. In the first set, the figure is filled in completely. In the second set, each figure has a one-centimeter-wide outline. In the third set, each figure has a one-millimeter-wide outline. Children select an inset shape and go through the stack of the first set of cards until they find the one that matches the shape. Then they place the inset exactly onto its matching card.

By placing the inset shapes onto the cards with thick to thin outlines, children are learning how an abstract symbol represents a concrete object. This is preparation for reading! If children can recognize and distinguish between a trapezoid and a parallelogram, they will be more likely to be able to distinguish two other shapes like a cursive b and a cursive z. When children have a lot of experience recognizing shapes, they will be more able to recognize the shapes they encounter in letters because symbols are shapes defined by lines. Think about the progression of abstraction from a filled-in trapezoid to the outline of a trapezoid, to the letter A.

Rich Language

As children are working with these shapes, our Preschool and Kindergarten teachers, Ms. Carr, Mrs. Berdick, Ms. Chiste, and Mrs. Rogers introduce vocabulary. Our young classrooms are alive with the rich vocabulary of quadrilaterals (rectangle, square, rhombus, parallelogram, isosceles trapezoid, right-angled trapezoid), curved figures (circle, oval, ellipse, quatrefoil), triangles (equilateral triangle, right-angled isosceles triangle, acute-angled isosceles triangle, obtuse-angled isosceles triangle, right-angled scalene triangle, acute-angled scalene triangle, obtuse-angled scalene triangle), and polygons (pentagon, hexagon, heptagon, octagon, nonagon, decagon). We offer them the exact names while our youngest learners absorb language effortlessly. For example, we say an acute-angled scalene triangle.

Memory Games

We also use the Geometry Cabinet to play a series of sensorial games that help children perfect their perceptions and make their mental classifications conscious. You saw similar games demonstrated during our Parent Discovery night in January.

In the first memory game, the geometry shapes and their apertures are mixed up between two locations in the room, far enough apart to allow more time for children to hold the memory of the shape as they move through various potential distractions to find the match. The second game is a little harder because the shapes are placed in scattered locations around the room. When children go to find a specific shape, they must retain the impression in their memory for a much longer time and not be distracted by the other images they are receiving. In this process, children are exercising their skills of memory and recognition.

The third memory game is one in which children try to find an object in the room that has the exact match of the shape. This experience allows children to move from working with the geometric qualities in their isolated form in the material to helping discover the qualities of the shapes in the world around them. They love getting a bowl as they look for circles or a hexagonal box to match with the hexagonal inset. Try this game together at home!

Learning through Mistakes

One of the aspects of authentic Montessori that I love is built-in controls for error. If a child tries to correspond a pentagon inset to a decagon card, there is immediate feedback, and the child can try again and again to find the match. The learner will explore the mistakes and corrections independently. Teachers will always observe when to step in if a key piece of information is necessary, but often experience is the best teacher

Multiple Benefits

While the main purpose of the Geometry Cabinet is to help children develop the visual discrimination of shapes (an important skill used in learning, especially reading), there are so many other benefits. The activity of tracing their fingers along the edges of the shapes and frames helps prepare children for using a pencil to make the shapes that form letters. Grasping the knobs helps them refine their pincer grasp. They learn important vocabulary. Because young children love shapes, they are driven to repeat this work which increases their concentration and focus.

A simple material with so many benefits, the Geometry Cabinet is a material worth coming to see. Schedule your school tour by clicking this link and see children interact with this foundational geometry material. We are currently enrolling children under four years of age for summer and next fall of 2024.

Current families are invited to observe in our preschool, elementary, and adolescent communities. You can schedule your classroom observation by clicking the green buttons below.