Perhaps it happens one day when your four-year-old comes home from school one day, excited to show you their work for the day. They proudly show you a perfectly-traced pentagon with elaborate, colorful patterns inside that they have created.

Maybe it’s when your eight-year-old casually references acute-angled scalene triangles.

Regardless of when it happens, as Montessori parents, there comes a moment when we become acutely -aware (pun intended) of our children’s interesting knowledge of geometry. We recall our own study of the subject beginning much later – likely sometime during our high school years. We notice that our children seem to be really ready for the information, which can feel surprising. Not only are they ready, but the work seems to fill them with joy and satisfaction.

What, exactly, is going on?

As with so many things, Montessori discovered that young children are fully capable, and in fact developmentally-primed, to learn about subjects that have traditionally been reserved for much older children. Geometry is a perfect example. Read on to discover what this portion of a Montessori education can offer your child.

The Primary Years

From ages 3-6 much of children’s geometry instruction in Montessori classrooms is indirect. That is to say that while they are practicing crucial developmental skills, they are often doing so through the lens of geometry preparation. One obvious example, as mentioned above, is with the metal insets. Children trace a variety of geometric figures including squares, triangles, circles, curvilinear triangles, and quatrefoils, among others. The main objective of this work is to prepare the child’s muscles for proper pencil grasp and handwriting. When they have mastered tracing, they work to create intricate designs within the figure.

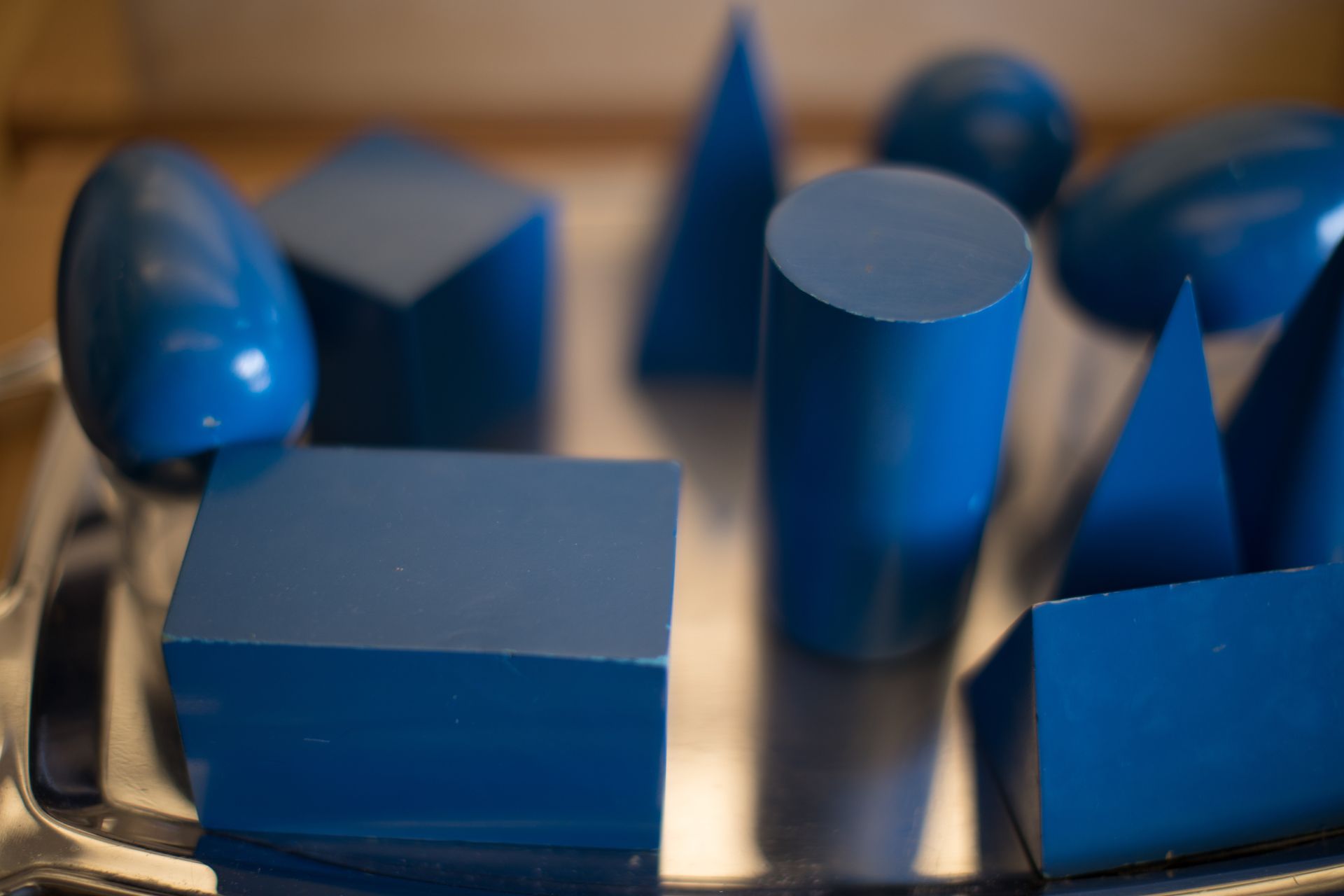

Primary students are also given a number of simple geometry lessons that allow them to begin naming figures and exploring shapes. Wooden geometric solids are held and named by the children (cube, sphere, square-based pyramid, etc.). The geometry cabinet is composed of drawers of related figures; small wooden insets are organized into a polygon drawer, curvilinear figure drawer, triangle drawer, and so on. Children also use constructive triangle boxes to manipulate triangles in order to form larger triangles and other geometric figures. The key during these early years is to give children some early exposure to geometry and allow them to use their hands to explore these concepts.

The Elementary Years

During the elementary years the Montessori geometry curriculum expands significantly. Teachers often begin by reviewing content taught during the primary years, but 6-year-olds are ready and eager for more. This begins with a detailed study of nomenclature.

Using a series of cards and booklets that correspond with lessons given by the teacher, children explore and can create their own nomenclature sets. Topics include basic concepts such as point, line, surface, and solid, but go on to teach more in-depth studies of lines, angles, plane figures, triangles, quadrilaterals, regular polygons, and circles. For example, when children learn about lines they begin by differentiating between straight and curved lines, but go on to learn concepts such as rays and line segments, positions (horizontal and vertical), relational positions of lines (parallel, divergent, perpendicular, etc.)

Throughout the second plane of development (ages 6-12) the study of geometry continues to spiral and go into more and more depth. Children as young as seven learn about types of angles and how to measure them. Eight year olds explore regular and irregular polygons, as well as congruency, similarity, and equivalency. In lower elementary children begin learning about perimeter, area, and volume.

In upper elementary, children begin to learn about the connections between the visual aspects of geometry and numerical expressions. They apply what they’ve learned about perimeter, area, and volume to measuring real-life objects – including Montessori materials they’ve seen in their classrooms since they were three years old. They learn about things like Fibonacci numbers, which combine their sense of number order with the appeal of geometric patterns.

Now, when your child comes home with surprising knowledge about geometry content, we hope you have a better idea of where they’re coming from. If you have any questions or would like to see this type of work in action, please give us a call.