We experience a lot of independence at Wheaton Montessori School. Interdependence is another vital aspect of our humanity and a key part of each of our learning communities.

All of us at Wheaton Montessori School and beyond depend on the help of other people. We are social beings and we evolved to be interdependent with our fellow human beings. None of us exist in isolation and together our children create communities in which each member thrives.

Interdependence is woven into how our classrooms operate and at the early elementary level we also have a material that provides children with a window into how humans depend upon each other.

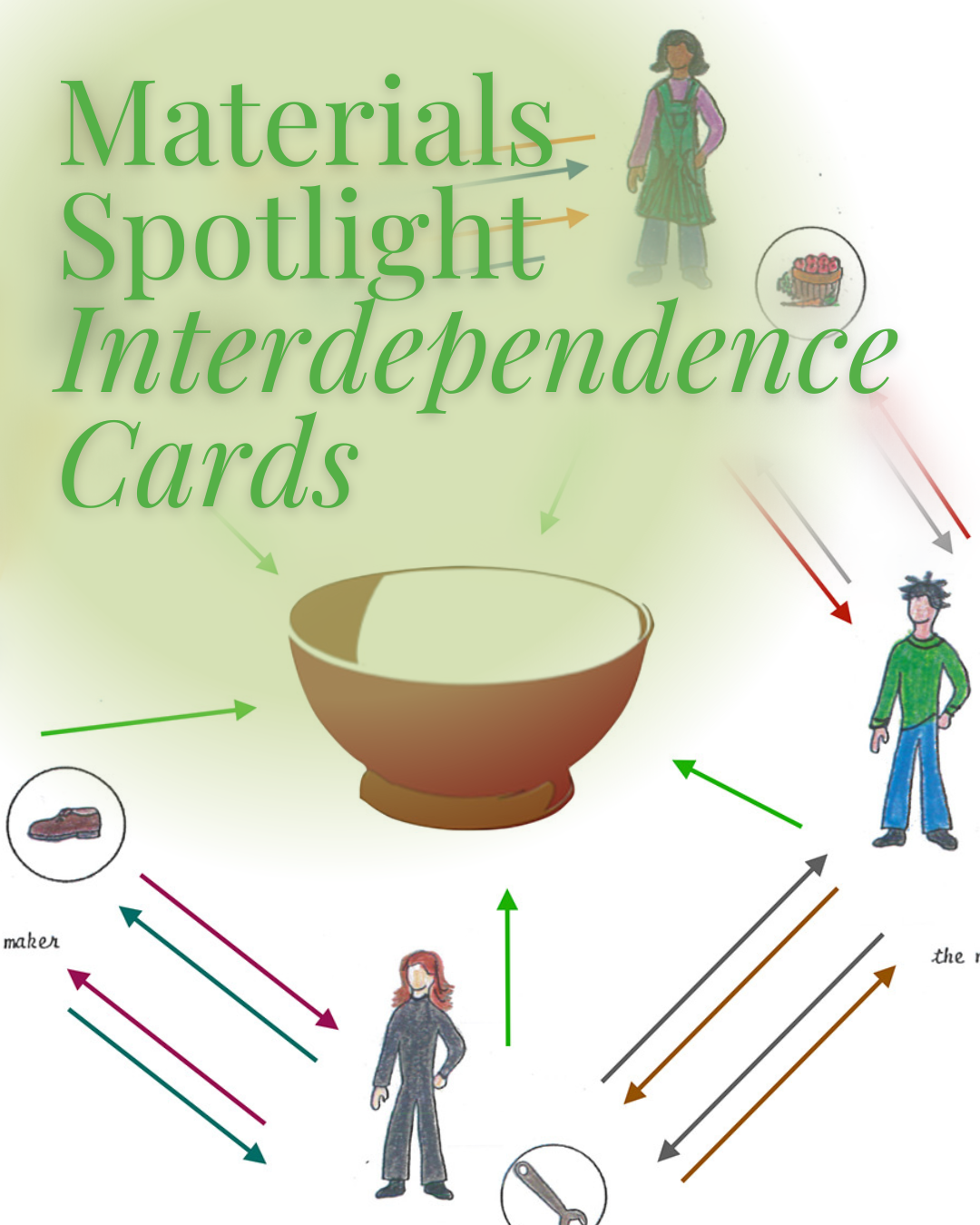

The Interdependencies Cards

To introduce this material, Suzanna Mayhugh and Tracy Fortun start by gathering a small group of children and asking about a recent meal or their favorite foods. When someone mentions bread, or that they ate toast that morning, we ask where the bread came from. Together the group follows the trail of origin of the food, exploring questions like: And where did the supermarket get the bread? Who baked the bread? From where did the baker get the flour? Finally, the trail leads back to the farmer.

As a group, we marvel at how many people it takes to bring bread to us. If the children are interested, we continue with other food or breakfast items, always arriving at the beginning when the farmer has planted the seeds.

At this point, our elementary students and teachers often go to the shelf and get the first set of Interdependencies cards.

Where do we get our food from?

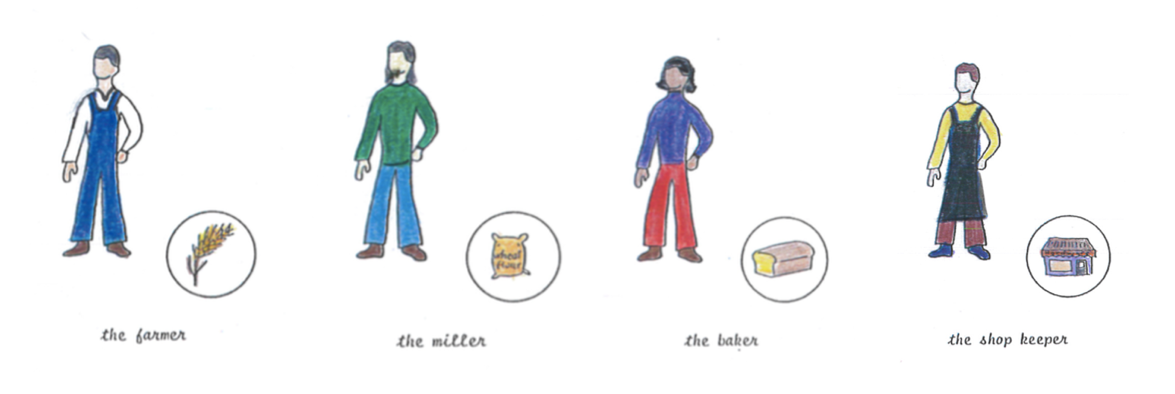

These cards provide a physical representation of the group’s discussion of the origin of our food. Because someone bought their bread at the supermarket, we place the “shopkeeper” card. We continue explaining how the shopkeeper bought the bread from the baker, placing the “baker” card to the left of the shopkeeper card. We continue the process until the array is complete: the farmer - the miller - the baker - the shopkeeper.

We comment on how many people are involved in the process before asking another question: How does the miller get wheat from the farmer?

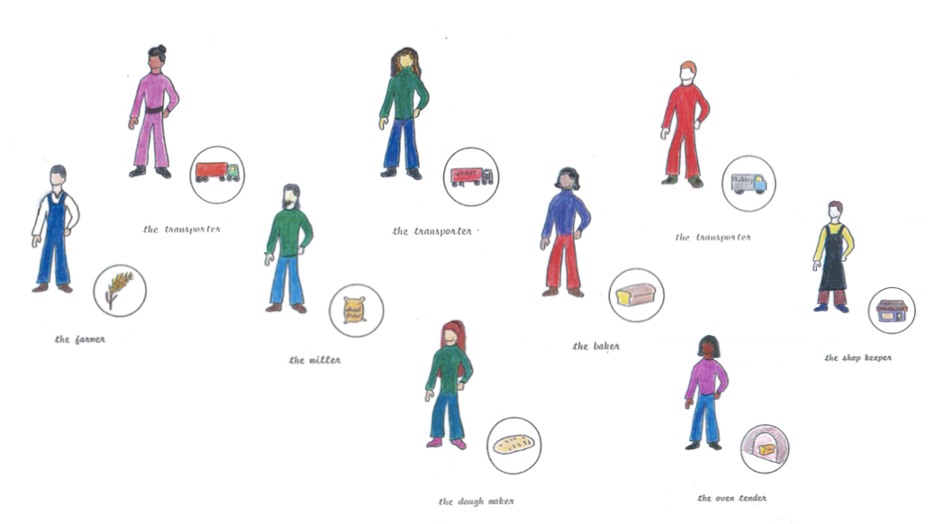

The children discuss and then we explore how the farmer needs some way to get the wheat to the miller. Perhaps a truck is used, or maybe a train, but some form of transport is needed. We then place the cards to represent that transportation and repeat for other producers.

Then we suggest thinking about the baker a little more. We explore if the baker needs help and can discuss adding a dough maker, oven tender, and packager around the baker card.

If the baker needs help, then likely the miller, farmer, and even the transporters need help, too! All these people work together to bring us our bread. What would it be like if we had to do it all for ourselves?

These interdependency exercises bring awareness to children in a developmentally appropriate way. Though the materials are intentionally quite simple, the children feel great satisfaction from using their reasoning minds to make the chain of production and human work apparent. The cards also help the children order the sequences we discuss.

Production & Exchange

In additional lessons, we use other sets of cards to explore what farmers produce, who depends upon the farmer, and who the farmer needs. When children have worked with these different sets of cards and explored the interconnections, we can use the cards to introduce how goods are exchanged among people and how the medium of exchange today is money.

We introduce this concept by thinking about how people generally can’t just trade what they produce. The baker, for example, won’t want shoes every day that the shoemaker needs bread! Thus, people invented money, which is exchanged instead. So, when the shoemaker needs bread, she gives the baker some money, and receives bread in return!

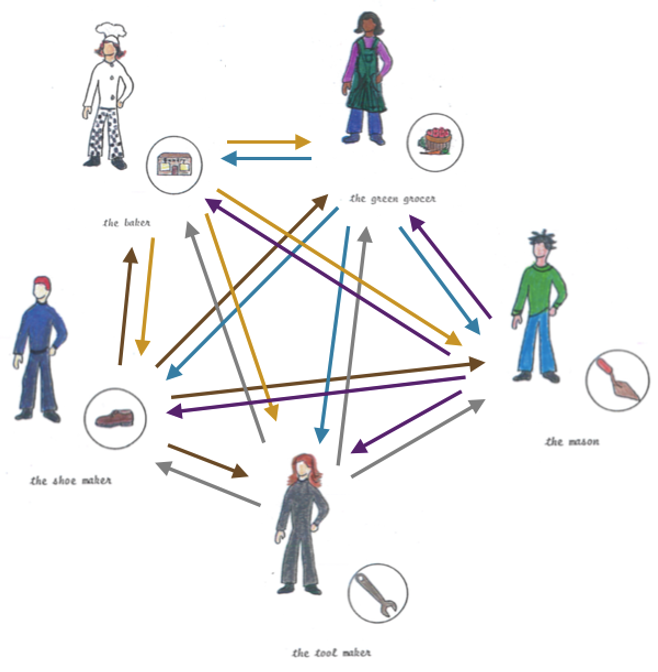

We continue in this manner, discussing various exchanges and visually representing the connections by drawing colored lines between the different producers to show how there is a complicated network of goods flowing from person to person and of money flowing in exchange.

Additional Services

Once children appreciate this initial introduction to economic exchange, we explore how each of the people on the cards also needs services like police, roads, water supply, garbage collection, libraries, and health services.

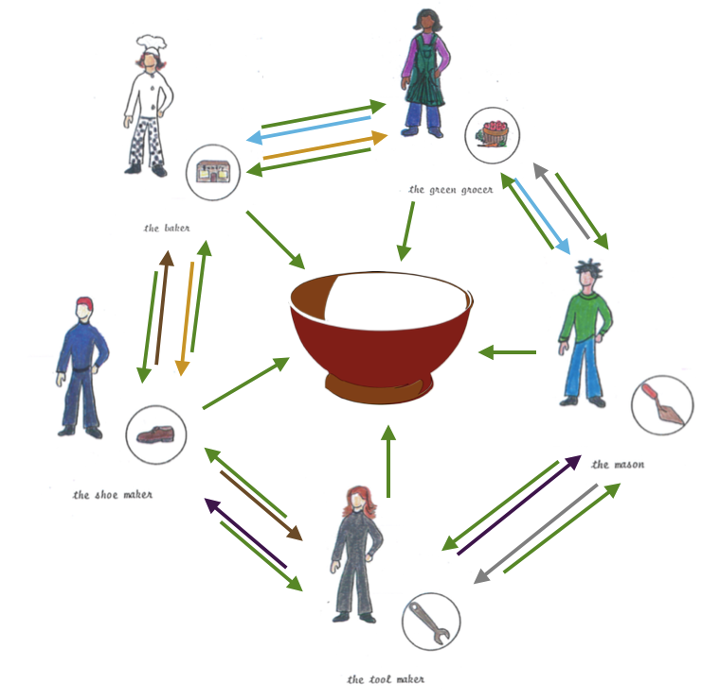

We talk about how people got together and decided to 'chip in' to pay for these services. Then in the center of the array of cards, we place a card showing a red bowl. We draw a green line to the bowl card and talk about how each person pays some money to a central collection agency. This money is called 'taxes', and the government uses tax money to provide services.

Young elementary students are often fascinated by this work and like to lay out the cards to show different models. Even older elementary students have ah-ha moments as they begin to understand economic concepts and the idea of what taxes represent. Sometimes children even want to make a set of interdependencies cards of their own for some product they choose. At other times children extend the work by organizing Going Out trips to a bakery or a farm. Our students usually want to make their own interdependency diagrams.

Our 4-6th grade students often use this as a jumping off point to investigate taxes. Who determines how and why tax money is spent? Ultimately, these lessons are one way that students will be lead to investigate local, state, and federal government.

Although the material we use to highlight interdependencies is relatively simple and seemingly unsophisticated, it is quite important. Plus, elementary children find the work intriguing and love the message the material conveys. Isn’t’ it amazing the way Dr. Maria Montessori planned to incrementally lead students to make discoveries? They learn academic information while they are reinforcing values of gratitude and appreciation.

Wheaton Montessori School’s community is dependent on its families, teachers, and donors. Our world will benefit when more young people are directly taught how humans are interconnected. Please come deepen your knowledge of Montessori elementary classrooms and share your experiences with others. Your Montessori experiences, monte-stories, will help change the future.

We love to share what we do through observations and tours:

Adolescent Seminar Observation

Ms. Searcy’s Upper Elementary Classroom Observation

Mrs. Fortun’s Lower Elementary Classroom Observation

Mrs. Mayhugh’s Lower Elementary Classroom Observation

Mrs. Berdick’s Primary Classroom Observation

Ms. Carr’s Primary Classroom Observation

Ms. Chiste’s Primary Classroom Observation

Mrs. Rogers’ Primary Classroom Observation

Schedule a tour by clicking this link to come visit our classrooms and see this and more skillfully designed activities in action. We are enrolling children who will be between 2.5 and 4 for summer and fall start dates and we will hold a space for enrolled students who have not quite reached 2.5.