Often we are asked how our highly trained teachers assess children’s work and progress without relying on quizzes, tests, or grades. If we remember that Montessori is about learning for life, we can flip this question and ask, how does assessment work when we move outside school walls and step into the world of work? In our work environments, do we have tests and grades? If so, how do they help us grow and improve in what we do?

Interestingly, a 1999 document “An Employer's Guide to Good Practices” from the U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration, has a whole chapter on issues and concerns with assessment, including the “limitations of tests in providing a consistently accurate and complete picture of an individual's related qualifications and potential.”

Dr. Montessori designed assessments that provide an accurate reflection of thinking and problem-solving?

It’s worth thinking about what we want to assess. Do we want students to just acquire new content knowledge or be able to apply this knowledge to new or existing situations? Do we want to see if students can produce something that demonstrates their understanding of the content or skill? Do we want to assess their writing ability, speaking skills, creativity, collaborative process, or organization?

If we focus on authentic assessments, we are asking that students apply what they have learned to a new situation, or perhaps we are requiring them to use some judgment to think about what information and skills are relevant and how they can be used. Similar to how adults are “tested” in work or personal life, often authentic assessments are tied to a real-world or complex situation.

In addition, authentic assessments offer students the opportunity to rehearse, practice, consult resources, and get feedback to refine what they are doing. Students can be innovative in this process and as a result, are often extremely self-motivated.

In our elementary and adolescent communities, authentic assessments may take the form of:

- Role-playing or performing a historical event and exploring what might have happened if things during that time had changed.

- Drawing a diagram of how a process works and showing what happens if a variable changes.

- Creating an advertisement or brochure to highlight qualities or review something learned.

- Writing a diary entry for a real or fictional character.

- Composing a poem, play, newspaper article, or persuasive letter to share important concepts.

- Writing a letter to a friend explaining a problem or technique.

- Insert your idea here.

Wheaton Montessori students love demonstrating what they have learned in creative, authentic ways. They present to their peers. They grapple with concepts. They even sometimes teach younger classmates.

But how do teachers keep track of this learning?

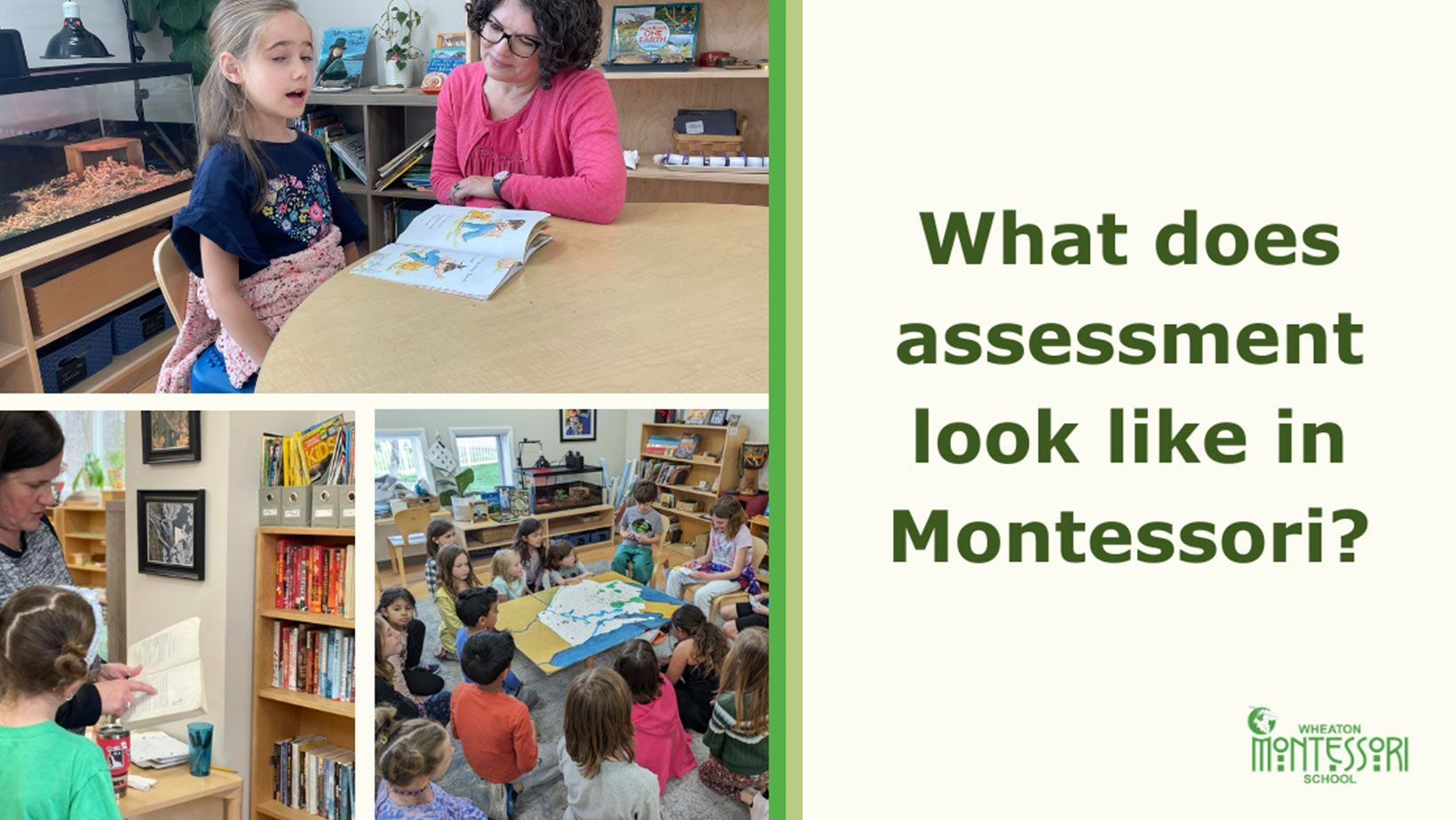

In addition to authentic assessment, our teachers are also using their extensive training in scientific observation techniques to understand students’ learning process, steps toward mastery, and needs for support. This is called formative assessment.

Formative assessment is a continuous, low-stakes, responsive process. This means that students are getting feedback and information while their learning is taking place. Through observation, the teacher is gauging students’ progress, determining what has been effective, and identifying what could be improved in the learning process. There are no grades involved, however the goal is mastery of the skill or content.

At all levels of Wheaton Montessori School’s classroom, formative assessment can look like:

- The guide observes students during a lesson presentation and the student’s independent follow-up work.

- Student reflection in work journals.

- One-on-one conferencing with the guide and the student.

- Discussion and review lesson of content or skills.

- Students informally or formally present their work.

- Student self-evaluations.

- Students correct their mistakes and reflect on what they learned from those mistakes.

- The teacher observes the student giving a lesson to another child.

Formative assessment doesn’t have to be teacher-driven. In fact, in Wheaton Montessori classrooms, students always get feedback and information about their learning from the classroom materials, many of which are designed to help children learn from their mistakes as they check their work. They don’t even have to be aware that they are learning through their mistakes.

Formative assessment is a collaborative process that happens “with” students rather than “to” students. Montessori students and teachers partner to get to know their strengths, interests, and needs. Because this is an ongoing, collaborative process, the teacher and students can make small, immediate, impactful decisions to support well-being, learning-goal achievement, and self-efficacy.

What are the results?

When students experience authentic and formative assessment as integral aspects of their education, they become self-directed learners because they are active agents in their learning process. This translates to agency in other environments and throughout life.

In Wheaton Montessori classrooms, we focus on getting an accurate and complete picture of children’s skills and potential. Contact the office to learn more about what this looks like in action!

If you have not toured yet, schedule soon. Spaces are limited for children who will be between 2.5 and 4 for summer and fall 2024 start dates. Prospective families can schedule a school tour by clicking on this link. This will be the perfect opportunity to explore our school, understand our curriculum and learning environment, and decide if it’s the right fit for your child.